What Would Ben Franklin Do?

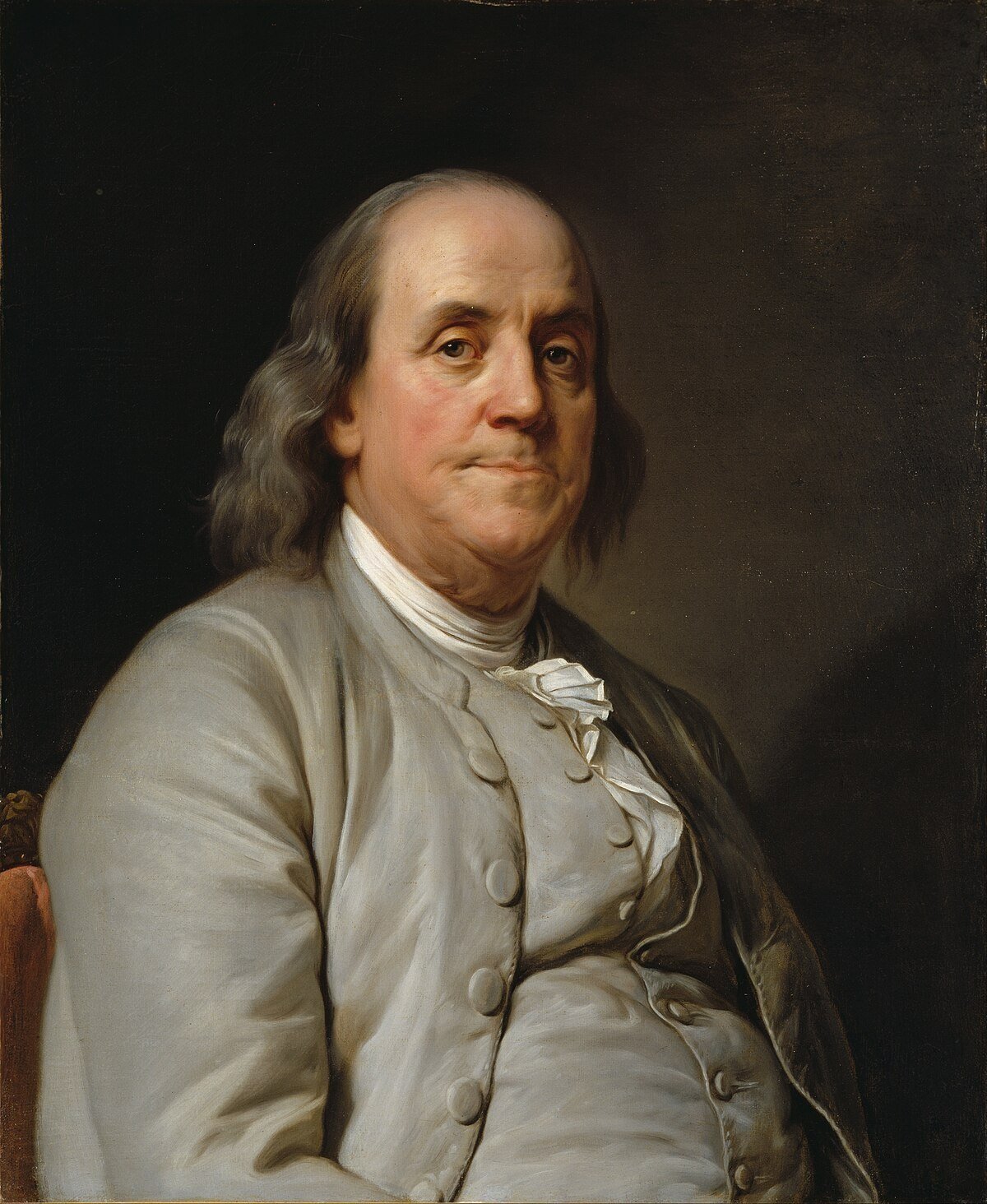

Portrait by Joseph Duplessis, 1785. National Portrait Gallery.

Benjamin Franklin Founder of the University of Pennsylvania

W W B F D ?

“Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as public liberty, without freedom of speech.”

The New-England Courant | July 9, 1722

-

At the age of 16, and still working as an apprentice printer to his brother James, Benjamin Franklin was already an advocate of free speech. These lines, written as Franklin’s earliest literary alter ego Mrs Silence Dogood, clearly show his commitment to its importance for good government.

Franklin was motivated to write by the imprisonment of his brother James for criticizing the Massachusetts government. At this time Britain’s North American colonies remained thinly populated and were often quite poor. Although the town of Boston had existed for almost eighty years, it only had 11,000 residents. Yet, it was the biggest city in the colonies. Colonial governments were well-established but were often plagued by factionalism. They also lacked the tax income they would need to extend their power. British rulers were not a lot of help in this regard; they had relied on private citizens to grow their American empire and even in 1720 were reluctant to throw men and money at securing their possessions.

In such circumstances, piracy flourished. Poor colonial governments welcomed pirates to town with their Spanish gold and their eagerness to spend it in Boston’s taverns and stores. Not only in Boston, but also in Philadelphia and Charleston, governors turned a blind eye to the exact origins of this money. When pirates were tried in court, the jurors couldn’t be trusted to mete out impartial justice either.

Many colonists, and the British authorities, became intensely frustrated with this state of affairs, in which certain people enriched themselves while blatantly breaking the law. Benjamin’s brother James was one such opponent of the Massachusetts government's warm embrace of pirates and their money. Since he had recently started printing a weekly newspaper, James Franklin used it to voice his opinion on the matter. On June 11,1722, the Courant had insinuated that the Massachusetts authorities were not making proper exertions to capture a pirate vessel reported to be off the coast.

Exasperated by this “High Affront” to their authority, the General Court ordered James Franklin to be put in prison for the remainder of the legislative session. In other words, they locked him up for criticizing their lax attitudes towards pirates. While a completely free press was not yet well-established in either the American colonies or Britain itself, this was nevertheless an aggressive move on the part of the General Court. Usually, printers and writers had to consistently libel someone or insult the King (which amounted to treason) to prompt government action.

During his brother’s imprisonment Benjamin managed the paper, and “made bold to give our Rulers some Rubs in it, which my Brother took very kindly, while others began to consider me…as a young Genius that had a Turn for Libelling & Satyr.” The eighth and ninth letters of Mrs Silence Dogood were two such “Rubs.” At the age of only 16, Benjamin Franklin was already speaking truth to power. His brother James would not be so supportive the next year, however, when Franklin turned his rebelliousness on him and ran away to Philadelphia. The rest, as they say, is history.

“Sell not virtue to purchase wealth, nor Liberty to purchase power.”

Poor Richard’s Almanack | 1738

-

After running away to Philadelphia it took a good amount of time for the young Franklin to find his feet. He suffered not a few setbacks to his progress, including on his first trip to London in 1724 where he was left high and dry by Pennsylvania governor William Keith. Keith had promised to introduce him to some important men in the British capital, but had let Franklin down and left him to fend for himself.

By the 1730s, however, Franklin was on an upward curve in the printing business and in Philadelphia society. He had taken over the failing newspaper of Samuel Keimer in 1729 and turned The Pennsylvania Gazette into a successful weekly newsheet. He was training other printers too - sending out young acolytes to colonial towns without newspapers, such as Charleston, South Carolina. Not satisfied with such accomplishments he had also founded the Library Company of Philadelphia. An organization designed to give tradesmen access to books and useful knowledge, it was open to all who could afford the modest cost of a share.

Franklin certainly wasn’t in danger of getting very wealthy from these virtuous and community-minded activities. Printing a newspaper did not guarantee a living. Most printers sold advertising space in their newspaper to break even. Many relied on contracts with the colonial government as official printers. Producing Almanacks was another regular source of income. Sold annually and made for a specific year, these small and cheap books were a handy guide to important religious dates, moon phases, tides, as well as useful information such as weights and measures and local statistics

So, when Franklin conceived of Poor Richard’s Almanack in 1732 he wasn’t creating something very novel. Rather, he was doing one of the many things he was really good at; taking an existing technology and improving it. His improvements at first centered on his inclusion of aphorisms in the almanack. Filling every spare space with these catchy sayings, Franklin turned the Almanack into a motivational text as well as a handy reference. Soon, he was publishing Poor Richard tailored for different colonies and selling 10,000 copies a year.

In order to generate the vast quantity of aphorisms he needed for this annual operation, Franklin relied on others. “Sell not virtue to purchase wealth, nor liberty to purchase power” was likely taken from one of the English compendiums, such as Thomas Fuller’s Collection of English Proverbs, that he consulted. Often, Franklin recycled his quotes, bringing them back in different publications and using alternative phrasing.

Consumers of his almanacks and pamphlets likely did not tire of these perennial sayings because they had (and still have) much to commend them. In the eighteenth century, as in the twenty-first, we wish for a government and society that is composed of morally upstanding individuals who are capable of devotion to the common good and are able to resist the allure of power and wealth for its own sake.

Pennsylvania Gazette | May 9, 1754

-

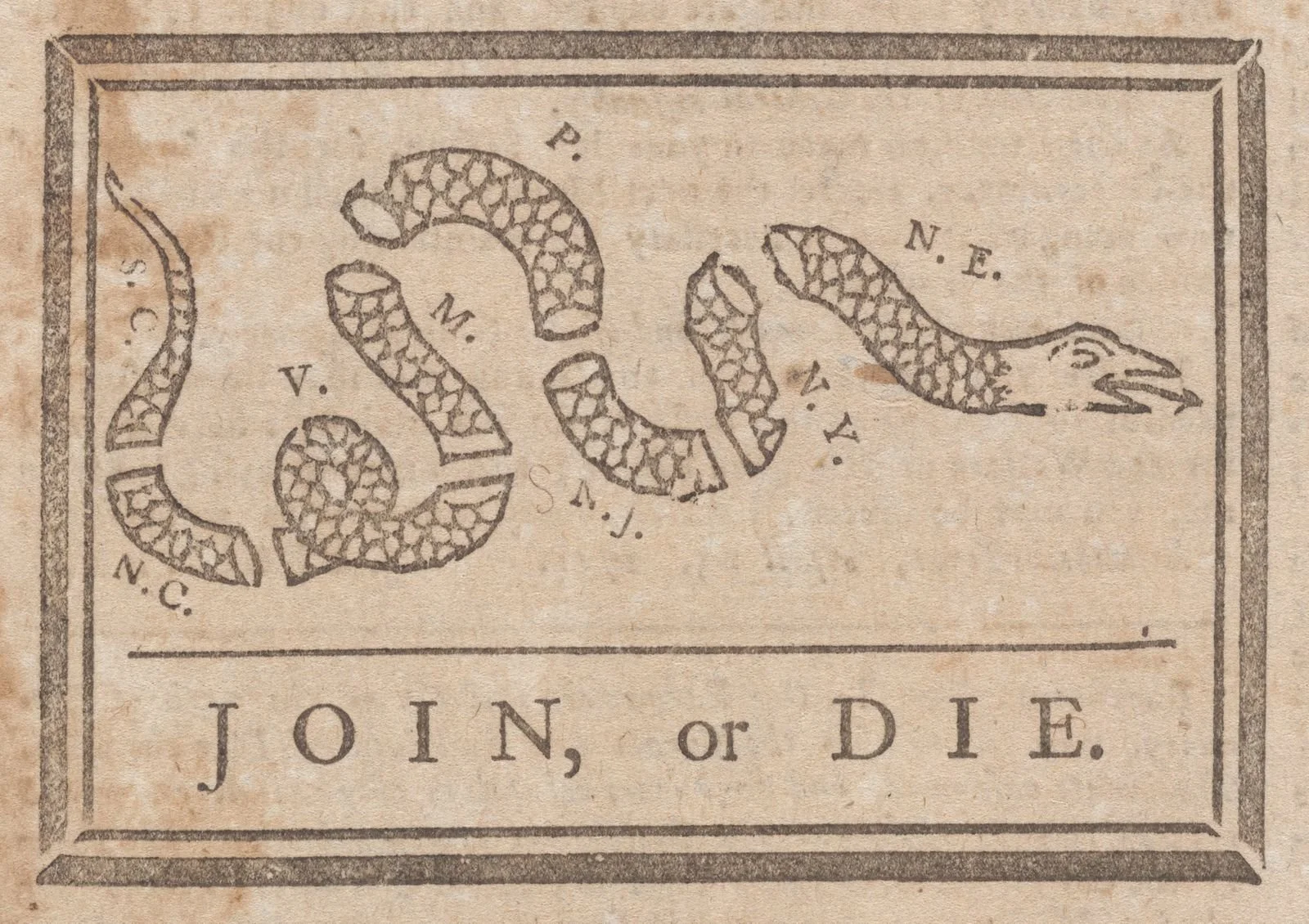

Benjamin Franklin’s “Join or Die” cartoon is considered by many scholars to be the first political cartoon published in a North American newspaper. Appearing for the first time in Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette in May 1754, it expressed the Philadelphia printer’s concerns that the political disunity of the British North American colonies might prove to be their undoing. Britain’s North American imperial rivals, the French, had recently forced the surrender of some badly outnumbered Virginia militiamen at Fort Trent, located at the forks of the Ohio River. Word of the defeat reached Franklin in early May, and he sent a copy of this engraving, along with a description of the danger presented by the French and their Native American allies, to his correspondent:

“The Confidence of the French in this Undertaking seems well-grounded on the present disunited State of the British Colonies, and the extreme Difficulty of bringing so many different Governments and Assemblies to agree in any speedy and effectual Measures for our common Defence and Security; while our Enemies have the very great Advantage of being under one Direction, with one Council, and one Purse.”

This description and the cartoon appeared the next day, May 9, 1754, in the Pennsylvania Gazette.

Franklin already had plans to serve as a delegate to a conference in Albany New York later that year. Attendees from seven British colonies at the Albany conference planned to discuss the need for cooperation in response to the French threat and the risk of losing the all-important British alliance with the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy (also known as the Iroquois or Six Nations Confederacy). His cartoon was quickly reprinted in several other colonial newspapers and reprised during the Stamp Act Controversy of 1765, one of the major conflicts with Britain that contributed to the movement towards North American independence.

If you turn the cartoon sideways, with the snake’s head pointing up, you can see that colonial parts of the snake mirror the sequence of colonies from north to south. The curves in the snake’s body also resemble the shape the eastern seaboard. Franklin also drew on colonial folk wisdom to add layers of meaning to his cartoon; popular belief had it that if one cut a snake into pieces it was capable of re-assembling itself and rising from the dead.